Brits could be just over a year away from receiving a ‘game-changer’ jab on the NHS to treat one of the deadliest forms of skin cancer.

Early results of the treatment — developed by pharma giants Moderna and MSD — found it drastically improved melanoma survival chances and could stop the cancer returning.

Now University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) is now leading the final phase of trials of the personalised mRNA jab, which scientists hope could also be used to stop lung, bladder and kidney cancer.

So how does it work? When will it be available? And could the treatment be used to treat other types of cancers?

Here MailOnline explains everything you need to know about the therapy.

What are mRNA vaccines?

While the science dates back to 2005, the first vaccines to use the mRNA technology were those made by BioNTech and Moderna against the Covid virus.

Messenger RNA, or mRNA, is a genetic blueprint that instructs cells to manufacture proteins in the body.

Unlike other traditional vaccines, a live or attenuated virus is not injected or required at any point.

For Covid, the mRNA vaccine instructed cells to make the spike protein found on the surface of the virus itself.

These harmless proteins ‘train’ the immune system to recognise the virus and then to make cells that fight it if someone later gets infected with the real thing.

How does the melanoma treatment work?

Known as mRNA-4157 (V940), the jab triggers the immune system to fight back against the patient’s specific type of cancer and tumour.

To create the treatment, a sample of tumour is removed during the patient’s surgery.

DNA sequencing is then carried out to identify proteins produced by cancer cells, known as neoantigens, that will trigger an immune response.

These are then used to create a personalised mRNA vaccine that tells the patient’s body to generate the tumour-specific neoantigen proteins.

Once injected, the immune system reacts to the proteins by creating fighter T cells which attack the tumour, killing the cancer cells.

The immune system should recognise any future rogue cells, hopefully stopping the cancer returning.

What have the trials shown?

Scientists have given trial participants the jab alongside an immunotherapy drug, pembrolizumab or Keytruda, that also helps the immune system kill cancer cells.

Data from the phase 2 trial published in December found people with serious high-risk melanomas who received the jab alongside Keytruda were almost half (49 per cent) as likely to die or have their cancer come back after three years than those who were given only Keytruda.

Patients received one milligram of the mRNA vaccine every three weeks for a maximum of nine doses, and 200 milligrams of Keytruda every three weeks (maximum 18 doses) for about a year.

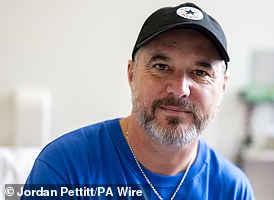

Dr Heather Shaw, national co-ordinating investigator for the UCLH trial, said there was real hope the therapy could be a ‘game-changer’, particularly as it appeared to have ‘relatively tolerable side effects’.

These include tiredness and a sore arm when the jab was given, she said, adding that for the majority of patients it appeared no worse than having a flu or Covid vaccine.

When will the jab be available?

The combined treatment is not yet available routinely on the NHS, outside of clinical trials.

But Stéphane Bancel, Moderna’s director general, believes that an mRNA vaccine for melanoma could be available in 2025.

The phase-three global trial will include a wider range of patients and researchers are hoping to recruit around 1,100 people.

At least 60 to 70 patients across eight UK centres — including in London, Manchester, Edinburgh and Leeds — are set to be recruited.

The twin therapy combination will also be tested in lung, bladder and kidney cancer.

The patients on trial must have had their high-risk melanoma surgically removed in the last 12 weeks to ensure the best result.

Dr Heather Shaw, national co-ordinating investigator for the trial, described it as ‘one of the most exciting things we’ve seen in a really long time’

Why is melanoma so deadly?

The disease occurs after the DNA in skin cells is damaged, triggering mutations that become cancerous.

Melanoma starts in cells called melanocytes. These make the pigment melanin, which gives the skin colour.

Around 15,000 Brits and 100,000 Americans are diagnosed with melanoma each year. It is the fifth most common cancer in the UK.

The incidence in Britain has risen faster than any other common cancer.

Increased UV exposure from the sun or tanning beds, has been blamed for the increase.

Despite huge strides forward in treatment that has seen survival leap from less than 50 per cent to more than 90 per cent in the past decade, it still kills more than 2,000 people a year.

Melanoma is often fast growing and can quickly burrow through the skin and into the blood vessels beneath. Once the cancer cells get into the bloodstream, the disease can spread throughout the body.

Patients with melanoma are offered surgery, especially if it’s found early. Radiotherapy, immunotherapy medicines and chemotherapy are also used.

Could the jabs work for other types of cancers?

Big pharma firms are all competing to produce successful cancer vaccines. Last May, BioNTech, in partnership with Roche, proposed a phase 1 clinical trial of a vaccine targeting pancreatic cancer.

The following month, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s conference, Transgene presented its conclusions concerning its viral vector vaccines against ENT [ears, nose and throat] and papillomavirus-linked cancers.

And in September, Ose Immunotherapeutics made headlines with its vaccine for advanced lung cancer.

Source: Mail Online