In March, Herron set a new women’s six-day world distance record at Further, Lululemon’s groundbreaking women’s-only ultramarathoning event in La Quinta, California (read more about Further here).Over those six days, she ran 560.33 miles—220 laps on a 2.56-mile course—shattering her previous personal best of 270 miles. And the 42-year-old has been in perimenopause for the past two years.

Part of a generation of professional athletes competing at a high level well into their 40s, Heron is outspoken about the impact of perimenopause—the gradual transition phase before the cessation of a person’s menstrual cycle—on her performance and well-being.

“I had no idea perimenopause existed until two years ago,” admits Heron, who has a master’s degree in health and exercise science and started experiencing symptoms such as extreme fatigue and irregular menstrual cycles when she turned 40.

Meaning “around menopause,” perimenopause refers to the hormonal changes leading up to the end of menstruation and reproduction capabilities. While the timeline varies by individual, perimenopause often starts in the late 30s or early 40s and lasts for several years until menopause, which is defined as when a person has not had a menstrual cycle for 12 consecutive months. During this transition period, dramatically fluctuating estrogen levels cause symptoms such as irregular menstrual cycles, hot flashes, night sweats, mood swings, sleep disturbances, and changes in menstrual flow.

Herron went public about her symptoms last year in an Instagram post, where she talked about how “there isn’t a blueprint of when and what someone will experience and knowing what the right solution(s) are.”

“I feel like women have held in this struggle all these years, and holding it in was making me struggle even more and impacting my mental health,” Herron says. “Just talking about it eased that burden.”

But in addition to feeling isolated and experiencing sudden changes in her body, she also feared a decline in performance.

“I want to help normal women know more about perimenopause and how to cope with it, but also how to manage it as an athlete,” she explains. “And even though I’m going through these hormonal changes, when I feel great, I feel really great.”

“Even though I’m going through these hormonal changes, when I feel great, I feel really great.”

How Camille Herron has adjusted her training for perimenopause

Herron credits her medical team and sports dietician for helping her develop strategies to dial in her training to minimize symptoms and maximize performance.

For her, one of the first signs of perimenopause was a high iron level, which was causing Heron fatigue, joint pain, and muscle weakness.

“Your period helps regulate your iron, but when you go through perimenopause, you’re not having your period as often, so it becomes harder to manage,” explains Heron. She also quit taking her oral contraceptive—a move she says also helped alleviate her symptoms—and started following the Root Cause protocol, an anti-inflammatory diet.

In addition to these lifestyle changes, she also cut back on running volume and distance.

In the weeks leading up to Further, she kept her mileage between 100 and 130 miles per week and did one “long” run of 2 hours and 10 minutes (just over 16 miles).

“For a six-day event, it was important for me to go into it being healthy and fresh and not be worn down from excessive mileage and long runs,” she explains. “I would be putting myself in a deficit if I went into that race beat down from overtraining.”

Instead, she focused on easy, low-heart rate mileage, running 11 to 13 times per week and walking three to five times for cumulative volume. She incorporated one or two weekly speedwork sessions into her runs to maintain turnover and burst speed.

She’s also been hitting the weight rack, doing heavy squats and deadlifts to build muscle strength needed for endurance events and improve her bone density—critical for women in perimenopause.

“Strength training helped bulletproof my body to withstand the stress of a six-day race.”

“I have a background in bone and muscle physiology, and I know how important strength is for women trying to prevent things like hip fractures,” she explains. “Strength training added another layer to help bulletproof my body to withstand the stress of a six-day race.”

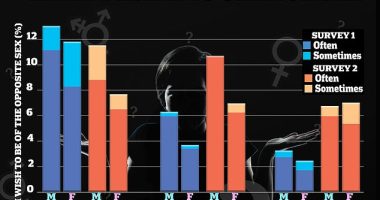

Leading up to and during the Further event, Lululemon made sure to partner with the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific so that Heron and the other athletes could participate in research and testing. The goal? To study female endurance biomechanics and performance and bridge the gender gap in sports research. In 2014, an audit of select sports science and sports medicine journals1 found that only 4 to 13 percent of published studies were female-only.

“Being a trained scientist myself, I was almost more excited about the science aspect than the running,” says Heron, who wore a Lululemon developmental shoe and other high-tech branded equipment, like a women’s-fit insulated cooling vest, during the event. Although the study’s full results won’t be released until fall 2024, she says specific tools, such as body temperature pills that alerted her to rising internal body temperature, helped her adjust her race strategy in real-time.

While Heron diligently planned for every aspect of the grueling endurance race, there was one variable she hadn’t planned on: getting her period. But irregular periods are common during perimenopause, and Heron didn’t let her body’s curveball phase her.

“I thought it would be more impactful because I was dealing with menstrual cramps, but my body became so broken down anyway, it was just one more thing to cope with,” she says, matter-of-factly.

“You can train at a high level, set world records, and get your period.”

“I hope it’s empowering and inspiring to other women that I was able to work through that and other symptoms of perimenopause during the race,” she says. “I run 130 miles a week, I get regular periods, and have had regular periods since I was a teenager. I really want to normalize that message that you can train at a high level, set world records, and get your period.”

Well+Good articles reference scientific, reliable, recent, robust studies to back up the information we share. You can trust us along your wellness journey.

- Costello, Joseph T et al. “Where are all the female participants in Sports and Exercise Medicine research?.” European journal of sport science vol. 14,8 (2014): 847-51. doi:10.1080/17461391.2014.911354

Source: Well and Good