This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Welcome back. Little by little, the door to EU membership is opening for Bosnia and Herzegovina. In principle, I welcome that — but I’m worried that, despite its undoubted good intentions, the EU is indulging in a certain make-believe in its policies towards the troubled former Yugoslav republic. You can find me at tony.barber@ft.com.

First, some housekeeping. The Europe Express weekend newsletter will take a pause over Easter. Normal service will resume on Saturday April 6.

Enlargement momentum

It’s almost 30 years since the end of the 1992-1995 war that tore apart Bosnia in what was, until Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the most violent conflict in Europe since the second world war. For most of these three decades, Bosnian membership of the EU has been a remote prospect — but the war in Ukraine is changing that.

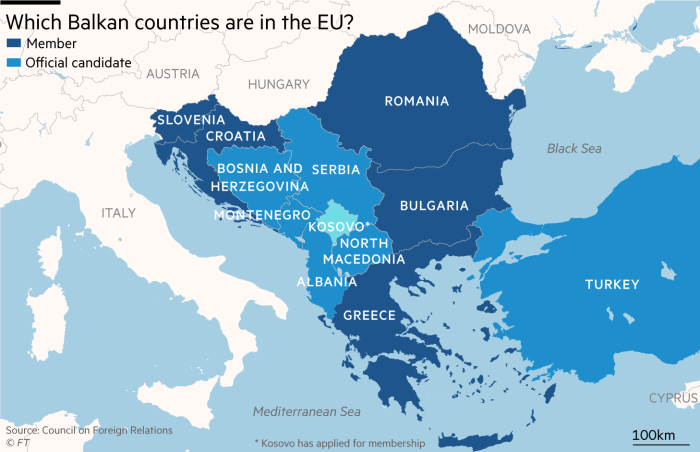

The geopolitical threats to Europe arising from the Ukraine war mean that there is now genuine momentum behind the EU’s efforts to expand its membership. The aim is to incorporate Ukraine, Moldova and even Georgia, as well as up to six Balkan countries — Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

As is well known, the enlargement process faces formidable obstacles. On one hand, the EU will need to make far-reaching changes to its institutions, finances and policies in order to accommodate all the aspiring members. There is little enthusiasm among the EU’s 27 governments for grasping this nettle until after June’s European parliament elections and the selection of a new European Commission.

On the other hand, the would-be entrants will have to reform themselves in order to be fit for membership. In theory, the group’s Balkan members have been on the road of reform since a summit in Thessaloniki in 2003 that held out, for the first time, an explicit promise of eventual EU admission.

But the reality is that, for most of the past two decades, the process of domestic Balkan reform has been slow — or, as in Serbia, has gone into reverse, notably in respect of adherence to democracy and the rule of law.

No country has joined the EU since Croatia in 2013. None is close to joining now. And, for unfortunate but compelling reasons, Bosnia is near the back of the queue.

Bosnia: progress or ‘complete hokum’?

Earlier this month, commission president Ursula von der Leyen recommended that EU governments should start formal membership talks with Bosnia. She stated:

Bosnia and Herzegovina has taken impressive steps forward. More progress has been achieved in just over a year than in a whole decade.

Von der Leyen cited Bosnia’s adoption of a law on conflicts of interest; a law on anti-money laundering and countering terrorist financing; improvements to the judicial system; efforts to fight corruption and organised crime; management of irregular migration; and alignment with EU foreign policy.

These look like useful steps, but not every expert on Bosnia is convinced. Jasmin Mujanović, a Sarajevo-born political scientist, wrote on the social media platform X that it was “complete hokum” to suggest Bosnia was making substantive progress on the EU’s membership criteria. He added:

“There is no process or logic; Brussels is making it up as it goes along.”

Put another way, the commission has strong geopolitical arguments for pushing forward Bosnia’s membership, but it knows that these are in themselves not enough to make EU accession happen. There are entry criteria that must be met — there is no getting round that.

So instead, the commission is choosing to foster the illusion that Bosnia is, at long last, on its way to transforming the institutions that since 1995 have made it the most politically paralysed, dysfunctional state in Europe.

Writing for the Foundation for European Progressive Studies, Dario D’Urso and Lada Vetrini observe:

In 2022, geopolitics replaced conditionality as the Council [of EU leaders] endorsed the commission recommendation to grant candidate status to Bosnia and Herzegovina . . . [It was] a political decision which, however, did not take into consideration the ongoing stalemate in Bosnia’s reform efforts.

Risk of violence

Some European leaders are well aware of the wishful thinking in Brussels. On the eve of an EU summit this week, Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte put it as politely as possible:

I think it is sensible that the commission has said that there has been progress since December . . . I don’t think that is enough to simply say now: start with accession negotiations.

The summit ended with a somewhat ambiguous decision to start the talks, but only once Bosnia has taken “all relevant steps” needed to get the process going.

Lack of reform may be just the tip of the iceberg in Bosnia. The latest edition [pdf] of the Annual Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community, published in February, says:

The western Balkans probably will face an increased risk of localised interethnic violence during 2024 …

Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik is taking provocative steps to neutralise international oversight in Bosnia and secure de facto secession for his Republika Srpska. His action could prompt leaders of the Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) population to bolster their own capacity to protect their interests and possibly lead to violent conflicts that could overwhelm peacekeeping forces.

Dodik receives support from Russia, whose main goal in Bosnia is to keep the state divided and outside western alliance systems.

Ethnic politics prevail

What’s gone wrong in Bosnia? For a succinct answer, look no further than the remarks of Željko Komšić, the Croat member of Bosnia’s collective presidency.

Speaking in September at the UN General Assembly, he said:

Bosnia and Herzegovina does not entail complete democracy, but rather a form of ethnocracy. Such a system, which guarantees participation in government to certain political actors and their ethnically based political parties, has the form of former and current totalitarian systems.

A superb analysis of what I have called “the dismal politics of ethnic partition” in Bosnia appeared in June in this essay by Berta López Domènech for the European Policy Centre think-tank.

She correctly identified the US-brokered 1995 Dayton peace accord as one of the chief causes of Bosnia’s unhappy situation today. She wrote:

In a country of slightly more than 3mn people . . . there are 13 parliaments, five presidents and around 150 ministries. Dayton allocated power along ethnic lines and granted veto rights to each constituent people — i.e., Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats …

Nationalist leaders have constantly abused the blocking mechanisms to boycott the normal functioning of the institutions, plunging Bosnia into a permanent state of political stalemate …

The division of the political system along ethnic lines has also paved the way for corrupt practices. The main nationalist parties . . . have benefited from the ethnically segregated system, capturing the state to serve their interests and consolidate their control over institutions and public companies.

These acute problems are reinforced by the weak sense of pan-Bosnian identity. Kristian Nielsen, writing for the Geneva Graduate Institute’s Albert Hirschman Centre of Democracy, explains:

Each of the main ethnicities — Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats — have a strong sense of self, and each have their own historical narratives, yet the overarching national identity remains contested.

Most Serbs and Croats identifying with neighbouring states (and often holding dual citizenship), rather than the one in which they live, only complicates this picture.

Democracy or stability in the Balkans?

Here is the central problem with the EU’s approach to potential Bosnian entry into the club. Democracy is a condition of membership but, by upholding Bosnia’s ethnically based political system, the EU may actually be entrenching anti-democratic tendencies.

This is the argument of a good recent report by the Clingendael Institute of the Netherlands, which detects similar problems across the Balkans:

The [western Balkan six] have slowly developed into “stabilitocracies”: countries with obvious democratic shortcomings that at the same time claim to work towards democratic reform and offer stability …

Engagement with political leaders rather than civil society in Bosnia and Herzegovina . . . hampers effective democratisation.

Court rulings

The European Court of Human Rights has ruled on several occasions that Bosnia’s political set-up discriminates against citizens who claim the right to democratic representation irrespective of their ethnicity. In a judgment in August (Kovačević vs. Bosnia and Herzegovina), the ECHR found that

. . . the current political system rendered ethnic considerations and/or representation more relevant than political, economic, social, philosophical and other considerations and thus amplified ethnic divisions in the country and undermined the democratic character of elections.

Future prospects

It’s true that, by adopting a step-by-step approach, the EU may be able to bestow some benefits of EU membership on Bosnia before it is ready for full accession.

It’s also true that, whatever the defects of Dayton, the peace accord did at least end the horrendous war of the 1990s.

However, if Bosnia and Herzegovina is to join the EU as a full member, its disastrous ethnically based political system will need to be thoroughly reformed.

Don’t forget the Balkans — a commentary by Ivan Vejvoda for Aspenia Online

Tony’s picks of the week

-

A pattern is becoming clear in India’s trade policy: access to the growing markets of the world’s fifth-largest economy will depend on offering something in return, the FT’s John Reed reports

-

Alexei Navalny challenged Vladimir Putin’s system of power in Russia and paid the price with his life, but why are there no equivalents of Navalny in China? — an analysis by Peter Fischer for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Recommended newsletters for you

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: europe.express@ft.com. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe

Read More: World News | Entertainment News | Celeb News

FT