Nick Baltas is head of cross-asset, commodities and stocks systematic trading strategies at Goldman Sachs, and a visiting researcher at Imperial College Business School.

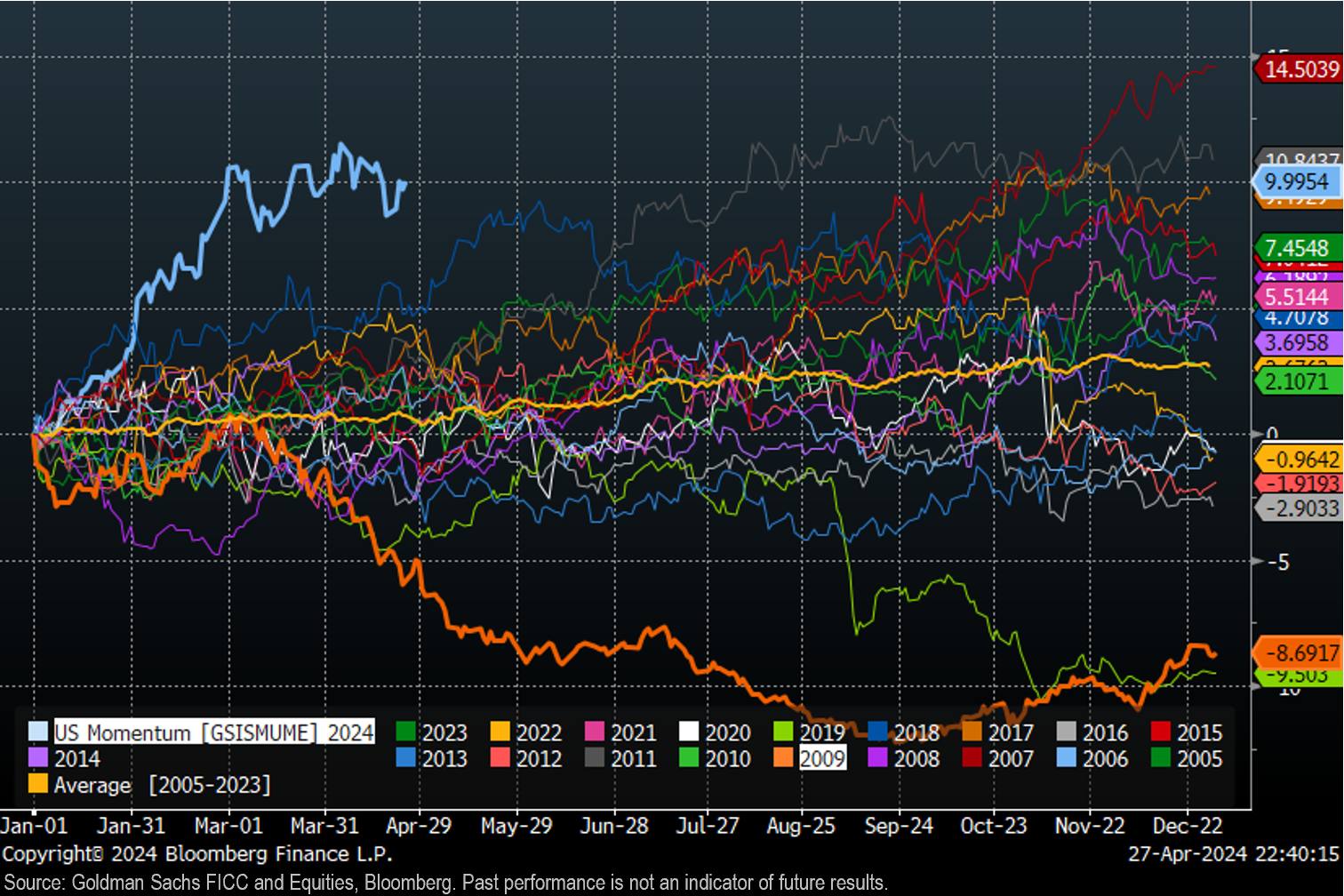

This has been a terrific start to the year for US equity market “momentum” — the phenomenon where winners keep winning and losers keep losing — thanks to the AI hype and bubbly tech stocks.

In fact, even after the recent wobbles it is still easily the best early-year performance we’ve seen from momentum in at least two decades:

This has naturally stirred fears around crowding and market concentration. Will the recent downturn escalate into a classic momentum crash, or will the momentum rally continue? Is it even possible for momentum investors to “time” a correction?

To answer these questions, we have to look at the origins of momentum — one of the more controversial financial market “factors” — and the implications of its divergent destabilising dynamics, due to its inherent lack of fundamental anchoring.

Momentum explained

Momentum describes the well-established empirical pattern of stocks that outperform their peers continuing doing so for a short period of time, hence extrapolating past outperformance. It’s been heavily studied in academia and is pervasive across all asset classes.

It’s somewhat controversial because it contradicts market efficiency — in principle, past information should have no forecasting value for future returns. It’s origin is therefore thought to be behavioural and linked to deep-seated investor biases, such as under-reaction to gradual diffusion of news, and subsequent overreaction, which causes the selling of winners too soon, while holding on losers for too long (the so-called disposition effect).

Mechanically, momentum trading exhibits a positive-feedback loop, as the demand for a stock increases the more it performs. However, the lack of a fundamental anchor — this is all about price action rather than a company’s underlying performance — can lead to heavily concentrated positions and reduced turnover, as past winners continue outperforming and symmetrically past losers continue underperforming in what resembles a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It is in these moments that inflows into the trade can have a destabilising effect and ultimately lead to a big fat collapse.

Centuries of stock data, even back to the Victorian era, confirm that momentum suffers from rare, but very aggressive “momentum crashes” following overcrowded periods, potentially justifying momentum profits as compensation for bearing such crash risk.

Over the last 100 years, the prime examples of such crashes occurred during the recovery period after the Great Depression in 1932 and the Global Financial Crisis in 2009, with the beaten-up losers strongly rebounding.

Given the behavioural underpinnings of momentum, maybe an analogy is the best ways to understand the complexities of timing a momentum crash following periods of strong performance and overcrowding. Let’s specifically compare a momentum trade to a party, inspired by Jeremy Stein’s presidential address at the American Finance Association 15 years ago (also in a video):

Complications arise when, in the process of pursuing a given trading strategy, arbitrageurs inflict negative externalities on one another [ . . .] The first [complication] might be termed a “crowded-trade” effect. [An arbitrageur] cannot know in real time exactly how many others are pursuing the same model and taking the same position as him. This [ . . .] creates a co-ordination problem and [ . . .] in some cases can result in prices being pushed further away from fundamentals.

The ignition of a momentum rally

In the search for amusement (financial returns), a young merrymaker (momentum trader) is constantly looking for parties (momentum trades). Critically, the earlier this person joins the bash (the emerging trends), the greater the accumulated fun (or returns, but you’ve probably got the point by now).

There’s a necessary condition for this activity to be successful; trivially, that other people join the party. Put differently, some form of early-stage crowding is necessary for social gatherings and strategies like momentum to perform. There are positive feedback loop mechanics at play: the demand to enter a party/momentum trade increases as it performs and gathers popularity, which leads to further crowding that in turn results in subsequent outperformance, and so on.

This is precisely the stage the current momentum trade finds itself in now, with the winning secular themes powering returns, investor interest and hedge fund positioning. Importantly, the level of amusement — especially in these later hours — can get further magnified in the presence of catalysts such as a few drinks and loud music (leverage).

Lord make me sober, but not yet

As crowds gather, and following a good performance run, an important consideration becomes progressively more obvious: when to “call it a trade” and exit? The party will deterministically come to an end. But can one time the exit to maximise the fun but minimise the hangover?

In principle, an early exit guarantees the avoidance of crash disappointment. However, it can produce disproportionate pain due to the fear of missing out on a late-hour continuation of the rally. After all, it sucks to leave a party just before it really takes off.

The equivalence here relates to the incentives that financial intermediation — ie the fact that wealth is typically managed via an intermediary, like an asset manager — imposes on momentum traders, who compete against each other for capital, and are by design adverse to redemptions.

Along these lines, they can’t afford missing a late-stage momentum rally when their competitors remain invested, even if they acknowledge the elevated crash risk. Perhaps paradoxically, staying invested can be considered a rational decision.

Taken together, it is not just about timing the exit, but rather acknowledging the implications of the opportunity cost in a competitive landscape.

The deterministic crash

A crash can be initiated by two types of effects:

— It can be an endogenous reason: that the catalyst of the amusement/returns simply ceases to exist. For example, funding liquidity drying out. This can cause fire sales and short squeezes when everyone runs for the exit.

— It can also be a more exogenous reason: a killjoy neighbour calls the police, or the music stops due to a power cut, causing the party to unexpectedly cease in a completely unforeseeable fashion. Or in a more staid financial context, a momentum trade can underperform if past winners suddenly underperform their peer group, or — which has historically been empirically more likely — losers suddenly and strongly rebound, catching up with the rest of the market.

After the strong momentum performance of 2024, investors scanning for catalysts for continuation or crash should assess the balance and intersection between the stickiness of secular winning themes like AI and the support (or lack thereof) in the second quarter earnings season. In any case, caution is warranted as accurately timing the exit is statistically impossible.

“Don’t fight the trend”

In the presence of FOMO dynamics and investment incentives, timing the exit is tantamount to market timing. The strong momentum rally in 2024 — perhaps the best systematic trade of the year so far — leaves investors with two choices:

1. Staying invested while deploying prudent risk management in the form of:

— Dynamically adjusting the exposure; such as reducing the overall leverage as the running risk of the momentum trade increases. This is like adding more ice or switching to water as the night drags on.

— Being more selective in the composition of a momentum trade and avoiding holding assets that become more prone to strong reversals (and specifically losers that are far from their 52-week highs, as they happen to exhibit strong rebounds as investor sentiment improves).

2. Completely hedging out their momentum exposure, even at the expense of potential short-term gains. This is even more relevant for traditional investors who might have accumulated momentum exposure as a byproduct of their main stock selection methodology.

All things considered, enjoy the ride for as long as it lasts, but try to minimise (if not possible to avoid) the hangover the morning after. This one could be a humdinger.

Read More: World News | Entertainment News | Celeb News

FT